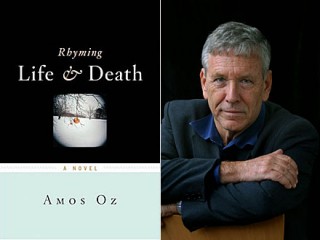

Amos Oz biography

Date of birth : 1939-05-04

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Jerusalem, Israel

Nationality : Israeli

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-11-27

Credited as : Writer and novelist, short story writer,

Gifted Israeli author, Amos Oz, achieved international regard as a novelist and short story writer, as well as the author of political nonfiction.

Born in 1939 to well-read parents who had emigrated from Europe several years earlier, Amos Oz grew up in a working-class neighborhood of Jerusalem. He received his primary education in a modern religious school. Oz was eight years old when Israel was became an independent nation. When he was 12, his mother committed suicide. Three years later, he left his home, at the age of 15, and joined a kibbutz (collective farm) near Tel Aviv. It was at this young age that Oz replaced his family surname, Klausner, with one of his own making: the Hebrew word for strength, "Oz." As a young adult, he studied at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he specialized in literature and philosophy. By the mid-1970s Oz was married with two daughters, living and working on the kibbutz while continuing his fictional and non-fictional writing.

Oz began publishing short stories in the early 1960s. These were included in his first collection of stories, Where the Jackals Howl, which received immediate critical acclaim. In this collection Oz revealed himself as a master craftsman, one who probes the emotional depths of his characters.

Although the collective physical and social structure of the kibbutz are well defined and drawn in his stories, Oz concentrates mostly on the fate of the individuals, their drives, ambitions, and idiosyncrasies. The dividing line between the normal and the pathological is very narrow in much of Oz's fiction, as in one of his first novels, My Michael.

In Elsewhere, Perhaps and the collection of three stories in the book The Hill of Evil Counsel we encounter Israeli pioneers who are dedicated to the land and to the ideal of building a new productive life. On the other hand, we also find that members of the kibbutz passionately crave to return to their native land, even at the price of abandoning their families. In Elsewhere, Perhaps, the wife of one of the settlers leaves her husband and returns to Germany with her former lover. In The Hill of Evil Counsel, the protagonist escapes with a British admiral, dealing a shocking blow to her family. In both the novel and the three stories, Oz proves himself a keen observer of human nature. He reveals an acute awareness of the turbulent events in the years immediately preceding the establishment of the Israeli state, stressing their impact on the life, ideas, and actions of the characters.

The obsession with time surfaces in Oz's Late Love, whose protagonist, perceives his life-mission as warning of Soviet plans to invade Israel. While formerly he was a fanatical believer in Communism and a devotee of the Soviet system, he now transfers his fixation on Israel.

Delusion is the main force prompting the enigmatic Lord Guillaume de Touron in Crusade, to set out on his journey to conquer Jerusalem. The crusaders veer from acts of cruelty and complete depravity to yearnings for spiritual salvation. The journey ends with death, as Touron realizes that his men were consumed by the evil spirit within themselves. In these stories and his subsequent novel Touch the Water, Touch the Wind, Oz depicts the existential condition of man caught up in the cataclysmic events of World War II, the holocaust and in the highly charged post-war political/social milieu of the Soviet Union and Israel.

The kibbutz is again the setting for Perfect Peace. Here Oz deals with the age-old problem of the clash between generations, the gap between ideals and reality and the need to come to terms with a given social and political order. Personal conflicts are the underlying theme in the novel Black Box. Oz uses the 18th-and early-19th-century epistolatory form to illuminate in the novel the inner lives of the characters and the twists of fate that overtake them.

Although primarily known as an author of fiction, Oz became very politically involved in Israel in the late 1960s, handing out pamphlets that promoted peace with Israel's Arab neighbors. This was not a popular position in Israel at the time, and at one point charges of treason were brought against him. As Christopher Price wrote in the October 20, 1995 New Statesman & Society, Israel's Six-Day war caused Oz to develop "a deep aversion to extremism and fanaticism, which he saw breeding pain and death; and an equally passionate positive belief in compromise. "One never knows whether compromise will work," [Oz] insists, "but it is better than political and religious fanaticism. Political courage involves the ability and the imagination to realize that some causes are worthwhile whether or not the battle is won or lost in the end."

Oz's many essays have covered political topics as well as literary ones. He has written extensively about Israel's Arab and Palestinian conflicts, always advocating a position of peace without reconciliation, i.e. the fighting can stop even while the separate nations remain separate and opposed. First published in 1979 in Hebrew, Under This Blazing Light, a collection of essays from 1962-78, was translated into English and published in 1995. As Stanley Poss wrote in Magill Book Reviews, these essays "reflect on what it means to live in a nation of five million surrounded by 100 million enemies," and can be regarded as variations on Oz's recurring theme, "Wherever there is a clash between right and right, a value higher than right ought to prevail, and this value is life itself."

Oz wrote an autobiography titled Panther in the Basement, published in 1997. Another work, In the Land of Israel (1983), describes nationalism as the curse of mankind. In The Slopes of Lebanon (1989) Oz looks at Israel's invasion of Lebanon and its reluctance to grant Lebanon statehood, writing "If only good and righteous peoples, with a clean record, deserved self-determination, we would have to suspend, starting at midnight tonight, the sovereignty of three-quarters of the nations of the world."

In 1992 Oz was awarded the German Publishers Peace Prize. In his acceptance speech, titled Peace and Love and Compromise and reprinted in the February, 1993, Harper's Magazine, Oz stated "Whenever I find that I agree with myself 100 percent, I don't write a story; I write an angry article telling my government what to do (not that it listens). But if I find more than just one argument in me, more than just one voice, it sometimes happens that the different voices develop into characters and then I know that I am pregnant with a story." This way he has kept his expressly political writing separate from his works of fiction.

Throughout his career Oz's fiction has been noted for its compassion, humanism and insight into human nature, as well as for its occasional fantasia and irony. Unto Death (1975), Touch the Water, Touch the Wind (1974), Elsewhere, Perhaps (1973), and The Hill of Evil Counsel (1978) each carry the complexity of Oz's themes, style, and form. Oz also tends to explore the dark side of life, exposing human follies and anguish, often in a farcical, grotesque fashion. But Oz's novels are also imbued with humanistic concerns despite the sardonic stance. His humanism pervades all his writings, including his topical essays and critical works, as in his series of Israeli interviews In the Land of Israel.

Although fluent in English, Oz has always written in Hebrew. E. E. Goode in the April 15, 1991 US News & World Report wrote that Oz "sees the Hebrew language as a volcano in action, a fluid tool for exploring the cracks in the dream." By 1993 his various books had been translated into 26 languages, his place in Israeli and world literature secure.

Amos Oz's works in English include My Michael (1972); Elsewhere, Perhaps (1973); Touch the Water, Touch the Wind (1974); the novellas Unto Death, Crusade, and Late Love (1975); The Hill of Evil Counsel (1978); Where the Jackals Howl (1981); In the Land of Israel (1983); and Perfect Peace (1985). Critical reviews include Robert Alter, "New Israeli Fiction," Commentary (June 1969), and Eisig Silberschlag, "From Renaissance to Renaissance II," Hebrew Literature in the Land of Israel 1870-1970 (1977).