Althea Gibson biography

Date of birth : 1927-08-25

Date of death : 2003-09-28

Birthplace : East Orange, New Jersey, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-07-13

Credited as : Tennis player and golfer, also a singer and actress,

5 votes so far

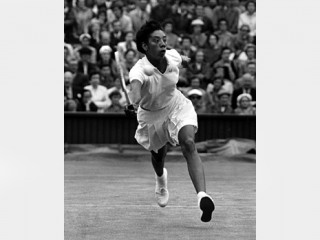

Althea Gibson's accomplishments in tennis rank among the most inspiring in modern professional sports. At a time when the game of tennis was completely dominated by whites, Gibson emerged with enough talent and determination to win multiple championships at Wimbledon and the U.S. Open in the late 1950s. Gibson was not only the first black woman to compete in these prestigious tournaments, she was also the first black person ever to win a tennis title. Having achieved national prominence in a sport long associated with upper-class whites, she became a role model for blacks of both sexes who sought the right to compete in previously segregated sporting events. Doors of opportunity that Gibson opened in both tennis and golf have been pursued by the likes of Arthur Ashe and Zena Garrison in tennis, and Calvin Peete in professional golf.

The titles of Gibson's two memoirs, I Always Wanted To Be Somebody, and So Much To Live For, serve as testimony to her personality and ambition. Her difficult childhood in a Harlem ghetto offered her little in the way of encouragement, but timely help from tennis coaches and supportive black professionals gave her opportunities never before extended to a black woman. Gibson forged into the previously all-white field of women's tennis with the conviction that racism could not stop her, and she handled difficult situations with a grace and earthy humor that brought her a firm following among American sports fans.

Chose Tennis Over Education

The oldest of five children, Althea Gibson was born in Silver, South Carolina, on April 25, 1927. At the time of her birth, her father was working as a sharecropper on a cotton farm. The crops failed several years in a row, and the impoverished Gibson family moved to New York City in 1930 where her aunt was said to have made a living by selling bootleg whiskey. There they settled in a small apartment in Harlem, and four more children were born.

In her memoirs Gibson described herself as a restless youngster who longed to "be somebody" but had little idea how to pursue that goal. School was not the answer for her. She often played hooky to go to the movies and had little rapport with her teachers. After finishing middle school, despite her truancy problems, she was promoted to the Yorkville Trade School. Her problems continued there and became so severe that she was referred to a series of social workers, some of whom threatened her with the prospect of reform school.

Solace was hard to find for the brash youngster. Movies and stage shows at the Apollo Theater offered a glimpse of another world beyond the crowded Harlem streets, and Gibson longed for that world--and her own independence. Even before she was of legal age to drop out of school she applied for working papers and quit attending her classes. She held a series of jobs but was not able to keep any of them very long. A promise to attend night school lasted through only two weeks of classes. By the time she was 14, Gibson was a ward of the New York City Welfare Department. The social workers helped her to find steady work, and they steered her into the local Police Athletic League sports programs.

Gibson's first contact with tennis was through the game of paddleball. The game is similar to conventional tennis but uses wooden paddles instead of rackets. In paddleball Gibson found a challenge she could answer. She would practice swatting balls against a wall for hours at a time, and before long she was winning local tournaments. Her prowess brought her to the attention of musician Buddy Walker, a part-time city recreation department employee. Walker encouraged her to switch to regular tennis and even bought her a racket--a second-hand model he re-strung himself. Walker also introduced Gibson to the members of the interracial New York Cosmopolitan Club. Some of them were also impressed with Gibson's natural talents, and they sponsored her for junior membership and private lessons with a professional named Fred Johnson.

The well-to-do members of the Cosmopolitan Club--particularly a socialite named Rhoda Smith--helped Gibson to curb her wild behavior and adopt a more reasonable and conservative lifestyle. Just one year after her lessons began in 1941, Gibson won her first important tournament, the New York State Open Championship. In 1943 she won the New York State Negro girls' singles championship, and in 1944 and 1945 captured the National Negro girls' championship.

Faced Racism in Professional Tennis

Even though she lost the 1946 Negro girls' championship, Gibson drew the backing of two quite influential patrons. A pair of surgeons, Dr. Hubert Eaton of Wilmington, North Carolina, and Dr. Robert Johnson of Lynchburg, Virginia, made Gibson an attractive offer. They would provide room and board for her and pay for her tennis lessons if she agreed to finish high school at the same time. Gibson accepted and moved to Wilmington to live with Eaton's family. There she attended the local public school and practiced her tennis moves on Eaton's private court. In the summertime she returned to Harlem for coaching by Fred Johnson. Beginning in 1948, Gibson won nine consecutive Negro national championships, a feat that quickly brought her recognition within the white tennis community as well.

Having finally realized the value of a good education, Gibson graduated tenth in her class at North Carolina's Williston Industrial High School in 1949. She then accepted a tennis scholarship to Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University in Tallahassee. She wanted to study music, as she could play the saxophone and had a fine singing voice. Counselors at the college persuaded her to stay with tennis, and she majored in physical education instead.

The biggest battle of Gibson's college years was securing the right to compete in major tennis tournaments against white opponents. That she had the talent to do so could not be denied, but many of the clubs that hosted major tournaments did not admit blacks. In 1950 Gibson sought an invitation from the United States Lawn Tennis Association to play in the National Grass Court championships at Forest Hills, Long Island. The invitation never came. Other tournaments at private clubs barred her as well. Frustrated but undefeated by the rampant racism, Gibson expressed her disappointment in a dignified and professional manner. Before too long she began to find allies in prominent positions.

One such ally was Alice Marble, an editor of American Lawn Tennis magazine. In the July 1950 issue of that periodical, Marble wrote a piece about the "color barrier" keeping Gibson from the top competitions. "The entrance of Negroes into national tennis is as inevitable as it has proven in baseball, in football, or in boxing; there is no denying so much talent," Marble contended. "The committee at Forest Hills has the power to stifle the efforts of one Althea Gibson, who may or may not be succeeded by others of her race who have equal or superior ability. They will knock at the door as she has done. Eventually the tennis world will rise up en masse to protest the injustices perpetrated by our policymakers. Eventually--why not now?"

Became Wimbledon Champion

The reaction to the editorial was almost instantaneous. Within one month of its publication, Gibson was invited to the national tournament at Forest Hills, as well as a number of other important competitions that had once been closed to her. In her first appearance at Forest Hills, Gibson advanced to the second round where she met Wimbledon champion Louise Brough. Gibson was leading in a tie-breaking set, 7-6, when play was interrupted by a severe thunderstorm. When the game resumed the next day, a frazzled Gibson--who had been hounded by the media throughout the delay--lost the match 9-7.

The following three years saw even greater disappointments. In 1952 Gibson was ranked seventh nationally in women's singles; the following year she dropped to 70th. Gibson seriously considered retiring from tennis completely, especially after she earned a Bachelor's degree in 1953, and took a teaching position at Lincoln University in Missouri. A former Harlem coach, Sydney Llewellyn, encouraged her to return to the circuit, and in 1955 she was chosen as one of four American women sent on a "good will" tennis tour of Southeast Asia and Mexico. In the months that followed those trips, Gibson also played in tournaments in Sweden, Germany, France, England, Italy, and Egypt, winning in 16 of 18 appearances. She raised her fortunes even higher in 1956 when she won her first major singles title at the French Open.

Black people seeking equal treatment in all walks of American life pointed proudly to the success of Althea Gibson in 1957 and 1958. The game of tennis has no more prestigious tournament than that held at Wimbledon in England every year. Not only was Gibson the first black ever to appear in that tournament, she was seeded first both years and won the Wimbledon singles and doubles championships both years. In 1957 Gibson defeated Darlene Hard in the singles competition, 6-3, 6-2, and then teamed with Hard in the victorious doubles match. Gibson returned to a ticker-tape parade in New York City and then proceeded to defeat her old nemesis Louise Brough at the U.S. national championships at Forest Hills. Returning to Wimbledon in 1958, she beat Great Britain's Angela Mortimer 8-6, 6-2 in singles and then paired with Brazilian star Maria Bueno for the doubles win. Yet another U.S. national championship followed that summer.

Sought Other Careers

It seemed that Gibson's future in tennis was quite secure by 1958. Although she had just turned 30, she was at the top of her game and had achieved international acclaim. Then she shocked the world by announcing her retirement from the sport. She admitted that the most pressing reason for her decision was money--she simply did not make enough playing tennis to meet her needs. In the wake of her announcement, Gibson began to earn far more by trading upon her fame. She embarked on a singing career that took her to the Ed Sullivan Show and led to the release of several albums; she received product endorsement contracts; she even appeared in a John Ford Western, The Horse Soldiers, with John Wayne and William Holden.

The lure of sports was a powerful one, however. By 1963 Gibson had embarked on another quest, just as ground-breaking as the first. She qualified for the Ladies Professional Golf Association and began competing in important golf tournaments--the first black woman to achieve that honor. Gibson never had the success with golf that she had with tennis, however. She never won a tournament and took home little prize money, although she participated in the LPGA tour from 1963 until 1967. As late as 1990, she attempted a comeback with the LPGA but failed to qualify.

In the 1970s and 1980s Gibson also served as a tennis coach and a mentor to athletes, especially young black women. Her views on modern tennis stars were solicited regularly, and she showed a particular admiration for Martina Navratilova. Having married a New Jersey businessman named William A. Darben, Gibson concentrated her efforts in Essex County, New Jersey, where she served for many years on the Park Commission. She also took posts with the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board and the Governor's Council on Physical Fitness. Darben and Gibson were divorced and Gibson later married Sidney Llewellyn. Gibson retired in 1992, save for personal appearances in connection with golf or tennis events.

No other black woman athlete has yet risen to the prominence in tennis that Gibson achieved in the 1950s where Gibson ultimately won 56 tournaments. In 1971 Gibson was elected to the Tennis Hall of Fame. In 1990 Zena Garrison advanced to the Wimbledon finals but was defeated; she was the only other black woman star to have advanced so far in the game by that time. This does not in any way diminish Althea Gibson's contribution to American sports. Her determination to play in the top tournaments at a time when blacks had little access to the exclusive tennis clubs helped to create a climate of acceptance that persists to this day. Elitism may never be completely eliminated in sports such as golf and tennis, but the contributions of Althea Gibson--and their effect on subsequent generations of black American athletes--are of lasting value to the sporting world.

Receieved Honors Late in Life

Gibson's health later started to fade, and by 1997, according to Time magazine, "Gibson [was] suffering in silence from a series of strokes and ailments brought on by a disease she [was] simply said to have described as 'terminal'." She had all but faded from the public's eye and it seemed she would die quiet and alone without anyone noticing. But some female athletes and coaches hearing about how she was living in all but poverty in East Orange, New Jersey, because her medical bills were overwhelming her, staged a benefit and tribute to the great Althea Gibson and raised, eventually, close to $100,000 to help defray the costs of her medical care. When Gibson learned of the effort that went into raising all the money to help her, her spirits were much lifted and her health improved somewhat.

In 1997 the Arthur Ashe Stadium was dedicated in New York to fellow black tennis great Arthur Ashe. The event took place on Gibson's 70th birthday and accolades were raised to her as well. In 1999 East Orange, New Jersey, dedicated the Althea Gibson Early Childhood Education Academy in Gibson's honor. The school's purpose, according to Tennis magazine, was to "provide kids ages six and under with a safe, nurturing environment in which to grow." Betty Debnaun, the principal of the new school said, "It's only fitting to name the school after a woman as great as Althea Gibson. She excelled in everything she did. She's a living legend." Also in 1999 a documentary of Gibson's life was published, an obvious indication that Gibson's accomplishments had not been forgotten. In 2000 The Sports Authority took upon itself to rank the ten top moments in women's sports. Gibson's becoming the first black woman to win Wimbledon and the U.S. Open was named one of the ten.

On September 28, 2003, Gibson died after a long illness of respiratory failure at East Orange General Hospital in New Jersey. She was 76-years-old. According to the Sports Network several hundred mourners showed up to pay their respects to Gibson. David Dinkins, former mayor of New York spoke at the service about her greatness. Among other things Dinkins reminded listeners of a very important fact: "A lot of folks stood on the shoulders of Althea Gibson." And this is something that people should never forget.

September 7, 2004: Gibson was honored posthumously at a ceremony at the U.S. Open tournament in New York.

August 27, 2007: Gibson was honored posthumously on the 50th anniversary of her victory at the U.S. Open in New York; tournament organizers named an award in her honor.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born on August 25, 1927, in Silver, South Carolina; died on September 28, 2003, in East Orange, New Jersey; daughter of Daniel (a mechanic) and Anna (Washington) Gibson; married William A. Darben, October 17, 1965 (divorced); married Sidney Llewellyn, April 11, 1983. Education: Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, BS, 1953.

AWARDS

Winner of national Negro girls' championships, 1944, 1945, 1948-56; winner of English singles and doubles championships at Wimbledon, 1957 and 1958; winner of U.S. national singles championships at Forest Hills, 1957 and 1958; named Woman Athlete of Yr., AP Poll, 1957-58; named to Lawn Tennis Hall of Fame and Tennis Mus., 1971, Black Athletes Hall of Fame, 1974, S.C. Hall of Fame, 1983, Fla. Sports Hall of Fame, 1984, Sports Hall of Fame of NJ, 1994.

CAREER

Tennis player, 1941-58; author, 1958, 1968; singer, musician, spokesperson for products, and actress, 1958-63; Ladies' Professional Golf Tour, golfer, 1963-67; tennis coach, member of athletic commissions, and associate of Essex County (NJ) Park Commission, c. 1970-92.

WORKS

* I Always Wanted To Be Somebody, Harper, 1958.

* So Much To Live For, Putnam, 1968.