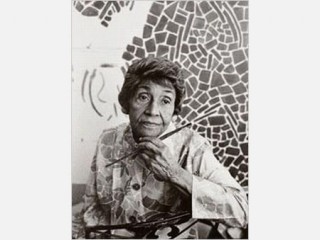

Alma Woodsey Thomas biography

Date of birth : 1891-09-22

Date of death : 1978-02-24

Birthplace : Columbus, Georgia

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-11-25

Credited as : Artist painter, ,

Abstract painter Alma Woodsey Thomas devoted her life to the youth of Washington and other local communities, both as a teacher and as an organizer of cultural events. In 1924 she became the first graduate of Howard University's School of Fine Arts. She possessed a natural sense of genius for color and form and upon retiring from teaching at age 68 embarked on a successful career as a professional artist.

Alma Woodsey Thomas was born on September 22, 1891, in Columbus, Georgia, she was the eldest of four daughters of John Maurice Harris, a teacher, and Amelia (Cantey) Thomas. Highly cultured and socially involved, the Thomas family owned a large Victorian home on 21st Street in Columbus's Rose Hill district, where Thomas was born and lived until the age of 15. As children, Thomas and her sisters enjoyed memorable visits to the home of their maternal grandparents, on a plantation near Fort Mitchell, Alabama. In her youth, she displayed a fondness for nature and the outdoors and enjoyed molding teacups and other pottery from the plentiful red Georgia clay.

The Thomas family remained in Georgia until the idyllic pace of life was disturbed by a period of racially motivated rioting in the fall of 1906. Unnerved by the violence, Thomas's parents took the family to Washington, D.C., arriving on July 31, 1907, after traveling by train from Georgia. They set up housekeeping at a new residence at 1530 15th Street NW, where Thomas was to live most of her life for the next 71 years, until her death in 1978.

Washington, like many of the southern United States, remained segregated in the early 1900s. Regardless, the Thomases anticipated better educational opportunities for their four children and greater cultural exposure for the family as a whole. Opportunities for employment were more plentiful too, for John Thomas as well as for his wife, who as a dress designer catered in her craft to the affluent women of Washington.

Talented in math and possessing an artistic bent, Thomas attended Armstrong Manual Training High School from 1907 to 1911, where she excelled in architectural drawing. For two years after high school she specialized in early child development at Miner Normal School, obtaining a teaching certificate in 1913. She took her first teaching job with the Princess Anne, Maryland, school district.

Two years later, in 1915 Thomas moved to Wilmington, Delaware, to the Thomas Garrett Settlement House. There she lived and worked at the community-operated school for resident children, teaching arts and crafts. She also devoted her time to making costumes for various school productions and to community arts productions.

In 1921 Thomas entered Howard University, initially contemplating a career in costume design. With that goal in mind she enrolled in a home economics program but changed paths by the end of her first semester, enrolling instead in the school's newly launched fine arts program at the urging of professor James V. Herring who recognized her talent and became her mentor.

Thomas's artwork during her years at Howard was founded almost exclusively in realism. In addition to many costume sketches and designs, she painted with oils and sculpted in ceramics. Also among her many three-dimensional works is the plaster "Bust of a Young Girl," completed around 1923, which is believed to be constructed in the image of her youngest sister, Fannie Cantey Thomas, then deceased. Among Thomas's most recognized works as a student is a still life done in oils in 1923. It is an untitled study depicting a vase with flowers; the bust of a woman appears to the right of the vase, in front of a draped background. Some experts believe that Thomas personally endowed the bust with the specific features and head covering that impart its distinctively African appearance and that the original model did not appear that way.

Thomas received a bachelor of fine arts degree in 1924, becoming the first ever to graduate from the Howard program. She moved briefly to Pennsylvania to teach at the Cheyney Training School for Teachers, returning to Washington after one term, to join the teaching staff at Shaw Junior High School. On February 2, 1925, she began teaching at Shaw, and in the process opened the door to a 35-year career at that school.

At Shaw, Thomas immersed herself totally in her life choices both as an educator and artist. She spent her summers in New York, at Teacher's College, Columbia University, where in 1934 she received a master's degree in fine arts education. In 1935 she summered in New York City as a student of England's premiere marionette maker, Tony Sarg. Thereafter she worked in collaboration with a Washington-based painter, Lois Mailou Jones, creating colorful string-operated puppets together. With Thomas contributing the design and fashioning the pieces of the puppets from balsa wood, Jones gave the toys a personality, using watercolors to paint faces on the wooden heads. Together the women created entire puppet troupes and sponsored performances at local venues such as the Phillis Wheatley Young Women's Christian Association and Howard University's Gallery of Art. Thomas produced popular children's classics—such as Alice in Wonderland —as puppet shows and wrote assorted scripts of her own. The need for these cultural events was especially acute because it came at a time in U.S. history when African American children were denied access to similar programs at the National Theater.

In 1936 she organized the Washington School Arts League. This program, also geared toward children of African American descent, was devised to sponsor and encourage tours, lectures, and other presentations at cultural venues such as museums and colleges. In 1938 she conceived of a program to create art galleries within the Washington schools. Beginning with a temporary exhibit at Shaw, she borrowed selected art works from the Howard Gallery and expanded the program from that starting point.

Thomas with her cultural influence made deep inroads into the Washington community, extending well beyond the youth programs with which she is most frequently associated. In 1943 she contributed to the efforts of two Howard professors, Herring and Alonzo J. Aden, to found the Barnett Aden Gallery at their residence at 126 Randolph Street NW. The gallery quickly found its niche in the Washington cultural scene and became a popular gathering place for local society. Barnett Aden attracted patrons from diverse social, political, and artistic backgrounds within the national capital. Near the end of the decade, Jones and Céline Tabary opened a more casual space, called "The Little Paris Studio," at Jones's 1220 Quincy Street NE residence. There, too, Thomas could be found frequently, not only with her students, but also relaxing in private.

As the Washington artistic community experienced major growth throughout the 1940s, Thomas in 1950, at age 59, enrolled at American University to continue her education and expand her study of art. A subsequent metamorphosis from full-time educator to full-time artist ensued. Her works from this early period are characterized as somber and heavy, both in color and mood. Blues and browns predominate, with rough, dense shapes. Among her many oils on canvas, she painted "Grandfather's House" in 1952, evoking the natural serenity of the Cantey homestead in Alabama. The complacent emotion of the plantation is represented predominantly in blues with heavy brown trees and foliage. The painting hangs at the Columbus Museum in Georgia.

The artist's evolution toward color and abstraction can be traced through the progression of her impressionist still life paintings. "Joe Summerford's Still Life Study," also dated 1952, is heavy with detail; dark shadows and olive tones are used freely. Her migration toward abstraction is foreshadowed only in the reflective surfaces such as the face of a clock and the glassy bulb of an empty vase. The objects appear on a table of brown wood, and the exposed background wall is brown also and significantly darker.

"Still Life with Chrysanthemums," from 1954, retains a sense of realism in the foreground objects while fading to abstraction with allusions to sun and foliage in the backdrop. By 1958, with "Blue and Brown Still Life," Thomas's reality fades into coherent blocks of color, while allowing for specific images such as the cat tossing yarn and the appearance of vessels in the background. The environment overall is noncommittal, in shades of browns and blues.

After spending the summer in Europe in 1958, Thomas's work underwent a gradual migration toward vivid color as she abandoned the use of oils, deferring to water-color. The browns were colorfully split apart to reveal the reds and yellows as seen in "City Lights" and "Yellow and Blue," both from 1959. Increasing levels of activity in the paintings are depicted by black brush strokes in the foreground, as reds emerge and sometimes overpower the backgrounds. This style is seen prominently in "Macy's Parade" and "Untitled Study" in red and green, both from 1960. Having retired on January 31 of that year, Thomas held a solo exhibition at Washington's Dupont Theatre Art Gallery from September through December. By 1961 her move toward abstraction and geometric form was all but complete with "Blue Abstraction."

Yet the total abandonment of impressionism was yet to be accomplished by Thomas. Her devotion to realism is vividly evident in "March on Washington," completed in 1964.

The painting, with its infusion of a socio-political backdrop, employs the new reds and yellows of her 1960s period, while reprising her moody blues from the 1950s. Thomas in fact participated in the August 28 March on Washington in 1963, and this work serves as her commentary.

Thomas in her signature style of later years employs an abundance of square stripes of acrylic color that flow about the canvas. Aerial views and bird's eye representations of trees, leaves, rivers, and brooks typify this period. Primary colors break forth from muted backgrounds, as in her 1969 "Azaleas." Also during these years she produced her Earth and Space series, including "Light Blue Nursery" and "The Eclipse," in 1968 and 1970, respectively.

Working from her first floor quarters in the same 15th Street NW home of her adolescence, Thomas was inspired most distinctively by a holly tree that grew within the view of a bay window in the living area. There, by means of the holly tree, the indoor world was insulated from the rush of traffic on the busy street outside, and her impressions of the holly tree surface repeatedly in the imagery of her brush-stroke patterns.

By the 1970s Thomas worked with increasing frequency on very large canvases of 72 by 52 inches, sometimes combining two or three of these large panels into a single image. Often she tied a strip of elastic around the frame as she painted, to guide the movement of the color. "Wind and Crepe Myrtle Concerto" and the paneled "Elysian Fields" from 1973 are typical of this phase of her art. A sense of movement characterizes her work from this time and is evident especially in the progression between the panels of "Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music" in 1976. News of Thomas's work, ripe with personal caché, seeped into the cosmopolitan art world in 1972 when the Whitney Museum in New York held a solo exhibit of her paintings. The Corcoran Gallery in Washington held a retrospective of her work that year, and in 1973 the Martha Jackson Gallery featured her work also as a solo exhibit.

Suffering from arthritis and having tripped and broken her hip at home in 1974, she was inactive for two years while convalescing. She resumed painting in 1976. A second exhibit at the Martha Jackson Gallery opened on October 23, 1976, and was in retrospect Thomas's final solo exhibition prior to her death in 1978. In all she was featured in 16 solo exhibitions from 1959 to 1976.

On February 24, 1978, she died at Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C., after emergency surgery to repair a damaged artery. She had carried her paint box and drawing pad with her to the hospital, where she arrived by ambulance. The luminous "Rainbow" of 1978 is her last known work.

Thomas defined both abstraction and impressionism on her own terms in the mid-twentieth century. She was a contemporary of those artists who comprised the Washington Color School of painting—including Gene Davis and Kenneth Noland—yet she rejected the practice of staining her canvases to create the void of relief that typifies that movement. Thomas's paintings in contrast forced texture to the forefront and her layered acrylics exhort the feel of the colors.

Alma W. Thomas: A Retrospective of the Paintings, Fort Wayne Museum of Art, 1998.

Foresta, Merry A., A Life in Art: Alma Thomas 1891-1978, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981.

Art in America, January 2002.

New York Times Biographical Edition, May 1972.

New York Times Biographical Service, February 1978.