Ali Akbar Khan biography

Date of birth : 1922-04-14

Date of death : 2009-06-18

Birthplace : East Bengal,Bangladesh

Nationality : Hindustani

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-12-06

Credited as : classical musician, sarod player, MacArthur Fellowship

0 votes so far

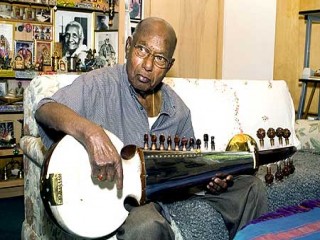

Ali Akbar Khan may be the "giant of Indian classical music," as the New York Times called him, but the five-time Grammy Award nominee has brought that music to a worldwide audience. The "undisputed master" of the sarod--a 25-stringed large plucked lute on which Indian songs known as ragas are played--Khan has been named by the Indian government as a National Living Treasure. Khan is a wildly prolific musician, performer, and teacher. With more than 95 albums to his credit, he maintains an extensive touring schedule and teaches at the three Ali Akbar Colleges of Music in California, India, and Switzerland. Recognized as "one of the greatest musicians of our time," according to the Washington Post, Khan has been awarded the highest arts honors in India and the United States and was the first Indian musician to receive the MacArthur Foundation's genius grant. "More than anything else," Robert Browning, executive director of the World Music Institute, told the New York Times, "he has built a knowledge of Indian music."

Ali Akbar Khansahib was born on April 14, 1922, in Shivpur, East Bengal (Bangladesh) to the Hindustani musician Allauddin Khan. Musical talent can be traced far back in Khan's family tree to Mian Tansen, a sixteenth-century musician in the court of North India Moghul Emperor Akbar. Khan began studying voice with his father and drums with his uncle at the age of three. His father trained him on many instruments but decided that he must concentrate on voice and on the sarod. Khan practiced the complex instrument 18 hours a day for the next 20 years. "I started to learn this music at the same time I began to talk," Khan told the Los Angeles Times. "So it is as natural to me as speaking. It's not something I have to think about any more than I have to think about the words I'm saying." The young musician made his first public performance at the age of 13. Khan continued his studies with his father until his father was over 100 years old, though the elder Khan often beat his son for what he saw as lack of dedication.

Khan was in his early twenties when he made his first recording and soon thereafter became the court musician to the Maharaja of Jodhpur, a post he held until the Maharaja's death seven years later. The state of Jodhpur gave Khan his first title as a young man, that of Ustad, or Master Musician. When Khan received the title, his father was humored. Khan's father's pride for his son was revealed much later. Late in his life, Allauddin Khan gave his son a title of his own, that of Swara Samrat, or Emperor of Melody. Khan understood his father's delayed praise for his skill on the sarod. "If you practice for ten years," he wrote in a concert program, as quoted in the Washington Post, "you may be begin to please yourself, after 20 years you may become a performer and please the audience, after 30 years you may please even your guru, but you must practice for many more years before you become a true artist--then you may even please God."

In addition to a prolific career as a recording artist and concert musician, Khan has composed and recorded music for films. His career as a composer began in India in 1953 with Aandhiyan by Chetan Anand. He went on to compose for House Holder, the first James Ivory and Ismail Merchant film, and Little Buddha by Bernardo Bertolucci.

Khan made his first visit to the United States in 1955 at the invitation of violinist Yehudi Menuhin, and he performed a concert at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He also made the first recording of Indian classical music on a Western record label and was the first Indian musician to perform on American television when he appeared on Alistair Cooke's Omnibus. Both engagements were well received. At first, Khan was a reluctant ambassador. "I didn't want to come at all," he told the Los Angeles Times. "I wanted to open a college in Calcutta.... And when I came here people didn't have any idea that India had some kind of classical music.... But I played and I liked the audiences, and I think they liked me." Celebrated for his intensity, Khan's lines "are vocalistic; they sing and sigh," wrote New York Times music critic Jon Pareles, reviewing a 1997 performance, adding, "even in its most exuberant moments, the music kept a reflective undertone." Another critic, quoted in the Los Angeles Times, called Khan's playing "so exquisitely pure, so serene, so painfully human or more than human, and so beautiful."

Khan's universal popularity bloomed in the mid-1960s when the Beatles discovered Indian music and brought it to the masses. In 1971, Khan joined his brother-in-law, famed sitarist Ravi Shankar who had also studied with Khan's father, onstage during George Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden. Though immensely popular, Khan later scorned the event as superficial, calling it "a monkey show."

In 1956, to pass along his knowledge of music, Khan founded the Ali Akbar College of Music in Calcutta, India. In 1965, he began teaching in America and was overwhelmed by the positive response from very talented Western students. Khan opened the Ali Akbar College of Music (AACM) in Marin County, California, in 1967 where he trained more than 10,000 Americans on the sarod and the tradition of Indian music. He later opened an extension of his music college in Basel, Switzerland. "I teach what I learned from my father," Khan told the Los Angeles Times. "The same system, with the same traditional purity. The same kind of devotion, the same love for music has to be built up. And that can only happen when it comes from the heart. Otherwise music doesn't last. It doesn't stay. It's like a medicine that doesn't work."

In 1997, Khan celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday, AACM's thirtieth anniversary, and performed at the United Nations in New York and at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. at celebrations of India's fiftieth year of independence. Also that year, he received the National Endowment for the Arts' National Heritage Fellowship--the nation's highest arts honor--presented by then-first lady Hillary Clinton at a White House ceremony. "These skills passed down from generations are irreplaceable," Clinton said, according to the Marin Independent Journal. "This reminds us that diversity is our strength and the arts are what bind us together."

Khan's honorary degrees include a degree of Doctor of Literature, Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta, India, in 1973; degree of Doctor of Literature, University of Dacca, Bangladesh, in 1974; degree of Doctor of Letters, University of Delhi, India, in 1984; doctorate degree, Viswa Bharati University in Shantiniketan, India, in 1998; and a degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, Honoris Causa, New England Conservatory of Music in Boston in 2000.

In the family tradition, Khan's son Alam began performing sarod publicly in 1998, and the two often perform together. In 1994, Khan founded the Baba Allauddin Institute to archive and preserve the vast collection of his father's written and recorded works. In 2001, at age 78, Khan still taught six classes a week for nine months out of the year. He also continued to tour the world extensively. "Every day I'm finding some new energy," he told the Los Angeles Times, "better ideas. The music gets younger as the body gets older. And one life is not enough to understand it all. My father used to say you have to be born ten times to get the music."

Khan was awarded the Padma Vibhushan in 1989, among other awards. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1991. In 1997, Khan received the National Endowment for the Arts' prestigious National Heritage Fellowship, the United States' highest honour in the traditional arts. Khan has received two Grammy nominations.

Selected discography:

-The Artistic Sound of Sarod , Chhanda Dhara, 1985.

-Journey , Triloka, 1990.

-Signature Series, Vol. 1 , AMMP, 1990.

-Signature Series, Vol. 2 , AMMP, 1990.

-Ustad Ali Akbar Khan Plays Alap, A Sarod Solo , Alam Madia, 1992.

-Garden of Dreams , Triloka, 1993.

-The Emperor of Sarod Live , Chhanda Dhara, 1994.

-Signature Series, Vol. 3 , Alam Madina, 1994.

-Signature Series, Vol. 4 , AMMP, 1994.

-Rag Manj Khammaj & Rag Misra Mand , AMMP, 1994.

-Live in San Francisco , AMMP, 1995.

-In Berkeley (live), AMMP, 1995.

-Jewels of Maihar , AMMP, 1995.

-Live in Calcutta, Vol. 1 , AMMP, 1995.

-Live in Calcutta, Vol. 2 , AMMP, 1995.

-In Concert at St. John's (live), AMMP, 1995.

-Live in Delhi , AMMP, 1995.

-In Eugene, Oregon (live), AMMP, 1995.

-Traditional Music of India , Prestige, 1995.

-Then and Now: The Music of the Masters Continues , Alam Madina, 1995.

-Morning Visions , AMMP, 1995.

-Passing on the Tradition (live), AMMP, 1997.

-Legacy: 16th-18th Century Music from India , AMMP, 1997.