Alexi Lalas biography

Date of birth : 1970-06-01

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Royal Oak, Michigan, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-07-06

Credited as : Soccer player, ,

3 votes so far

Holed up in a London hotel, Alexi Lalas spent the 1992 winter holidays alone, figuring soccer had dismissed him from its elite ranks. Months earlier, the promise of playing for a premiere British soccer club lured him abroad, but it was clear now that the English did not want the long-haired Yank. Without soccer, Lalas was just another unemployed, Generation X English major looking for a job. "What the hell am I going to do?" he wondered at the time.

What he did was return to America, back to his home on Woodland Street, in Birmingham, Michigan. But before he had time to fill out a job application, officials from the U.S. National Soccer Team called; they knew Lalas, a star at Rutgers University and a soccer Olympian, and they wanted to look at his talent. Lalas promptly flew west to try out in California. U.S. National Team coach Bora Milutinovic was impressed with Lalas---but only mildly so. He extended Lalas this conditional invitation: So long as you improve and cut your hair, you may train with the U.S. team. Lalas signed a one-month contract then went to the barber.

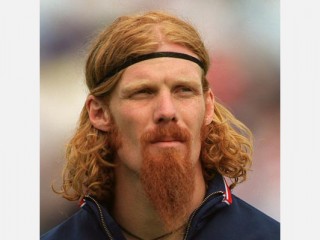

Eighteen months later, as the World Cup got underway, Lalas had lifted himself off the substitute bench. Fame came to him at a fast and furious pace. On the field, he was a starter, a stand-out defender and one of the team's highest scorers. Off the field, he was a celebrity who charmed the press with his whimsy and colorful character. His story made for good copy. After all, what other tournament player was a member of a traveling rock band and sported a tattoo on his ankle, an unruly mop of red hair on his head, and a scruffy goatee on his chin? An instant media darling, Lalas was dubbed everything from "Buffalo Bill" and "General Custer" to a "road warrior." He appeared on the Tonight Show with Jay Leno, ABC's Wide World of Sports, and CNN's Cutting Edge, and was featured on the pages of countless newspapers and magazines, including Sports Illustrated, the New York Times, Newsweek, Life, and USA Today. With each World Cup game, his glory grew as he successfully defended some of the globe's finest soccer players. "Whatever happens," wrote Phil Hersh of the Chicago Tribune, "Lalas will remain one for the books, a classic example of the instant stardom that can come to someone whose story is a little different."

Born in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oak, Michigan, soccer entered Lalas's life after his parents divorced. He was six when they split, and he moved to Athens, Greece, with his father, Demetrius, who landed a job teaching mechanical engineering. While abroad, Alexi did as the Greeks did and learned soccer. Four years later, he returned to Michigan to live with his mother and younger brother, Greg, in Birmingham. During the spring and summer he played on a local youth soccer travel team; in the winter, he turned to his first sporting love, ice hockey. He attended Cranbrook Kingswood High School, a prestigious prep school in nearby Bloomfield Hills. Although at Cranbrook Lalas refused to become a single-sport specialist, he nevertheless excelled on the ice, leading his team to a state championship, and on the soccer field, where he was named Michigan player of the year. In his athletic success, Lalas took after his maternal grandfather, Henry W. Harding, whose success as a football player at Hamilton College earned him recognition from Sports Illustrated. When it came time for Alexi to go to college, he looked long and hard for a school willing to give him an athletic scholarship. He took the first and only offer that came along.

At Rutgers University in New Jersey, Lalas continued to play hockey and soccer. Then, after his sophomore year, convinced that soccer was his calling, Lalas quit his college hockey team. Two years later, as a senior, he was rewarded for his full-time commitment when he was unanimously named the college soccer player of the year, winning the Hermann Award, soccer's equivalent of football's famed Heisman Trophy.

It was no surprise that Lalas was recruited by the U.S. national team after his graduation. He played in the Pan American Games in Cuba and was a member of the 1992 U.S. Olympic team. In many ways, the Olympics turned out to be a disappointment for Lalas; one week before the Games, Lalas broke his left foot. The injury undoubtedly limited his performance in Spain, when the Americans tied Poland 2-2. While he did manage to play 45 minutes in Barcelona, Lalas slipped into anonymity shortly after the Olympics.

Looking for a career as a professional soccer player, Lalas headed to Europe. During the fall, he tried out with the Arsenals, an elite British club. Lalas waited around a couple months, but didn't make the cut. "I was sitting in a hotel room in London, all alone doing nothing," he told the New York Times Magazine. "I had no team. If you're not an established international player, coming from the United States you have no credentials; you just sort of bum around and try to find someone to pick you up."

If competitive soccer had disappeared from Lalas's life then, it's not likely that he would've landed a job flipping burgers at McDonalds or Burger King, as he often joked with journalists. More probably he would've plunged wholeheartedly into the world of rock and roll music. He took an early interest in music, learning the piano as a kid, singing in choirs and barbershop quartets, and taking in interest in writing, much like his mother, a poet and publisher. Later, in college, he taught himself the guitar and formed a rock band, the Gypsies. The group played at small clubs in New Jersey and New York City, and released a 12-song CD on the Alexi Lalas label. Lalas himself composed the songs and invested $1,600 to press 1,000 copies. When a reporter from the Detroit Free Press once asked Lalas how the CDs were selling, he replied, "Let's see, what comes after tin? I think we've gone to nickel."

Of course, soccer didn't turn Lalas onto the street. Shortly after he returned to the States, he was recruited for the U.S. national team. As difficult as it was, he obeyed his coach and cut his shoulder-length hair. "It was a test," he told the Free Press. "Here I was, a 22-year-old punk, and Bora wanted to see how serious I was about soccer. For me to cut my hair was a big deal. I was really mad, but I wanted to play so badly. I would have run through LA naked if that's what it took."

When the World Cup arrived, Lalas's locks had grown back, and then some. When reporters covered the team's stunning 2-1 upset over Colombia during the first-round action, Lalas's quick wit and distinctive appearance played prominently in the game stories. In a Sports Illustrated article, for example, writer Alexander Wolff had this to say in his opening paragraphs: "Not a week earlier the international consensus was simple: The U.S. wouldn't have been in the World Cup at all if the host country didn't get an automatic berth. Now, suddenly, headline writers were calling the victory a MIRACLE ON GRASS, although no one on the American team wanted any part of that characterization. 'A miracle is when a baby survives a plane crash,' said Alexi Lalas, the U.S. Defender who looks like the love child of Rasputin and Phyllis Diller."

Weeks later, when the U.S. fell to Brazil 1-0 in the second-round, single elimination phase of the tournament, Wolff again found a quote from Lalas to open his story. "Going into Monday's game in the Round of 16, the U.S. had not only failed to beat the Brazilians in 64 years but also hadn't so much as scored a goal against Brazil since 1930, when the U.S. lost 4-3 in the first World Cup. But once this game kicked off, matters were out of the organizer's hands and the fireworks were free to start. 'If we lose, nobody cares,' said Alexi Lalas, the goateed American defender who's only a top hat and tails away from passing as Uncle Sam. 'That is what we are supposed to do. But if Brazil loses....'"

If Wolff's thumbnail sketch of Lalas seemed slightly softer and more distinguished than his earlier account---Uncle Sam is, by most accounts, a step up from Rasputin and Phyllis Diller---he wasn't alone. In the time that the U.S. team played four World Cup games, Lalas had wooed his critics, the observers who questioned whether Lalas's defensive skills matched the sharpness of wit. Possibly Lalas was just soccer's version of tennis star Andre Agassi, another flamboyant, Image-is-Everything kid who was also curiously passionate about cherry Slurpees and rock and roll music. As one French reporter noted, "In France, they would take [Lalas] for a crazy man. At best, for a likable original. At worst, for the Antichrist....What would they do with this neo-beatnik from Detroit who lights up clubs with his traveling rock band at an hour when the sports ethos says you should be asleep, dreaming of little balls?"

Lalas was candid about his failings. "There are definitely guys on this team who have more skill in their pinky than I'll ever have in my whole life," he told Steve Dilbeck of the San Bernardino Sun. "The key is to recognize your abilities and not overextend yourself. I work hard to clog the middle, to mark my man, to clear out to those people who have more ability." In another interview, he told People magazine, "It may not always be pretty. But I work my ass off and get the job done."

That work ethic paid off: Lalas outperformed the other American defenders during the World Cup, dispelling his critics. Journalists and fans alike hounded Lalas like no other American player. "I haven't seen this kind of craze with the fans since I've been with the team," goal keeper Tony Meola told USA Today. Meanwhile, as Phil Hersh of the Chicago Tribune observed, "The spotlight of the World Cup has brought out the best in Lalas, both as a celebrity and player. He has flinched from neither the demands of constant attention nor those of playing against some of the world's best attackers....He has played so well U.S. coach Bora Milutinovic broke with his philosophy of never commenting on individuals to heap praise on Lalas last week. 'If he plays the same way, he has a chance to be the best defender in the World Cup.'"

Lalas certainly established himself as the best defender on the U.S. team. Months later, he flew abroad, looking once again for a position on a professional European team. This time, he was besieged by offers. The English wanted him. The Germans wanted him. The Italians wanted him. And for a reported sum of $350,000 a year, the Italians got him. According to Soccer America magazine, "Terms of the deal were not disclosed, but Padova [the Italian Serie A team that signed Lalas] is believed to have paid a loan fee to the U.S. Soccer Federation of approximately $100,000, and Lalas's salary will be more than $250,000 per year. His rights are retained by U.S. Soccer."

Lalas moved to Italy during the summer of 1994. There he was greeted with more enthusiasm than he had enjoyed in America. "There were all these fans, with banners and singers and scarves, the whole bit," he told Soccer America. "In the middle of the questions, they started a 'Lalas' cheer!"

Once in Italy, Lalas established himself as a formidable player. One Italian sports daily newspaper named him the team's MVP during an opening match. For Lalas, the award was simply one more kudo to toss to his naysayers. "Through my career," Lalas told Reuters news agency, "people have said there's no way you can play on the Olympic team, there's no way you can play on the national team, there's no way you can play in the World Cup and have success. But you know, here I am."

June 2005: Lalas was named president and general manager of the New York-New Jersey MetroStars of Major League Soccer.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born Panayotis Alexander Lalas, June 1, 1970, in Royal Oak, MI; son of Demetrius Peter Lalas (a mechanical engineer and meteorologist) and Ann Woodworth (a publisher). Education: Graduated from Cranbrook Kingswood High School, 1987; Rutgers University, B.A. in English, 1991. Addresses: Publicist---U.S. Soccer Federation, 1801-1811 S. Prairie Ave., Chicago, IL, 60616.

AWARDS

Named Michigan high school soccer player of the year, 1987; named to Atlantic 10 All-Conference team, 1989; named Atlantic 10 Conference Eastern Division player of the year; 1991; Hermann Trophy, 1991; named Missouri Athletic Club player of the year, 1991.

CAREER

Played soccer and ice hockey at Cranbrook Kingswood High School in Bloomfield Hills, MI, 1983-87; captained high school ice hockey, 1987; earned athletic scholarship to Rutgers State University, 1987; leading scorer, Rutgers men's varsity ice hockey team, 1988; captained Rutgers' soccer team, 1987-89; captained the West squad to a gold medal at the 1989 U.S. Olympic Festival; member, gold-medal-winning U.S. team at Pan American games, 1991; member of the 1992 U.S. Olympic Team; member U.S. World Cup team, 1994; member Italian Serie A team (Pavoda), 1994; played for Ecuadorian team Emelec during the MLS off-season, 1998.