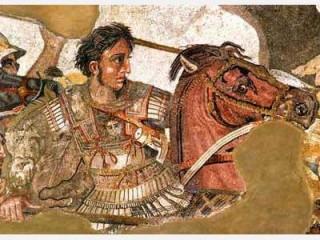

Alexander The Great biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Pella, Macedon

Nationality : Macedonian

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-08-18

Credited as : King of Macedon, member of the Argead Dynasty, philosopher Aristotle

7 votes so far

He is the most celebrated member of the Argead Dynasty and created one of the largest empires in ancient history. Born in Pella in 356 BC, Alexander was tutored by the famed philosopher Aristotle, succeeded his father Philip II of Macedon to the throne in 336 BC after the King was assassinated, and died thirteen years later at the age of 32. Although both Alexander's reign and empire were short-lived, the cultural impact of his conquests lasted for centuries. Alexander was known to be undefeated in battle and is considered one of the most successful commanders of all time. He is one of the most famous figures of antiquity, and is remembered for his tactical ability, for his conquests, and for spreading Greek culture into the East, marking the beginning of Hellenistic civilization.

Though the Romans would rule more land, no one man has ever subdued as much territory in as short a period as Alexander the Great, or Alexander III of Macedon, who conquered most of the known world before his death at age 32. Yet Alexander did more than win battles: trained in the classic traditions of Greece, he brought an enlightened form of leadership to the regions he conquered. His empire might have been a truly magnificent one if he had lived; as it was, he ensured that the influence of Greece reached far beyond its borders, leaving an indelible mark.

Macedon was a rough, warlike country to the north of Greece, and though the Macedonians considered themselves part of the Greek tradition, the Greeks tended to look down on them as rude and unschooled. But Greece's own day of glory had passed, and Alexander's father, Philip II (382-336 B.C.; r. 359-336 B.C.), subdued all of southwestern Europe between 354 and 339 B.C. At the age of 17, Alexander himself led the Macedonian force that conquered Thebes.

Philip, who revolutionized infantry tactics, might well be remembered as the greatest of Macedonian rulers, had he not been eclipsed by his son. Also remarkable was Alexander's mother, Olympias, who brought up her boy on stories of gods and heroes. Under her influence, he became enamored with the figure of Achilles from Homer's Iliad, and came to see his later exploits as fulfillment of the heroic legacy passed down by his mother. A third and significant influence was Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), who tutored Alexander in his teen years. It is an intriguing fact that one of the ancient world's wisest men taught its greatest military leader, and no doubt Alexander gained a wide exposure to the world under Aristotle's instruction.

He was not, however, a thinker but a doer. A natural athlete, Alexander proved his combination of mental and physical agility when at the age of 12 he tamed a wild horse no one else could ride. Alexander named the horse Bucephalus, and the two would be companions almost for life: later, when Bucephalus died during Alexander's campaign in India, he would name a city for his beloved horse.

Soon after Philip took control of Greece, he was assassinated, and in claiming the throne, Alexander had to gain the support of the Macedonian nobility. He did so with a minimum of bloodshed, establishing a policy he would pursue as ruler of all Greece: leaving as much good will as he could behind him, he was thus able to push forward.

Alexander next turned to consolidation of his power in Greece, which he did by a lightning-quick movement in which he captured Thebes and killed some 6,000 of its defenders. After that, he faced no serious opposition from the city-states, and embarked on a mission that had been Philip's dream: conquest of the vast Persian Empire to the east. The latter had once threatened Greece, only to be defeated in the Persian Wars (499-449 B.C.); now Greece, led by Macedon, would take control of the Persians' declining empire.

The main body of Alexander's army, some 40,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry, moved into Asia Minor while their commander crossed the Hellespont with a smaller contingent so that he could go on a personal pilgrimage to the site of Troy. Eventually, Alexander and his army passed through the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordian. In that city was a chariot tied with a rope so intricately knotted that no one could untie it. According to legend, the fabled King Midas or Mita (fl. 725 B.C.) had tied the Gordian Knot, and whoever could untie it would go on to rule the world. Alexander simply cut the knot.

After a successful military engagement against a Greek mercenary named Memnon, Alexander moved down into Cilicia, the area where Asia Minor meets Asia. The Persian emperor Darius III (d. 330 B.C.) came to meet him with a force of 140,000, and at one point--because Alexander's armies were moving so fast--cut him off from his supply lines. Darius chose to wait it out, letting Alexander's forces come to him, and Alexander, taking this as a sign of weakness, charged on the Persians. Alexander nearly got himself killed, but the Battle of Issus was a decisive victory for the Greeks. Darius fled, leaving Alexander in control of the entire western portion of the Persians' empire.

Instead of raping and pillaging, as any number of other commanders would have allowed their troops to do, Alexander ordered his armies to make a disciplined movement through conquered territories. In 332 and 331 B.C., Alexander's forces secured their hold over southwestern Asia, and by the latter year he was in Egypt, where he founded the city of Alexandria, destined to become a center of Greek learning for centuries to come. In October 331 B.C., he met a Persian force of some 250,000 troops--five times the size of his own army--at the Assyrian city of Gaugamela. It was an overwhelming victory for the Greeks, and though Darius escaped once again, he would later be assassinated by one of his own people.

Alexander now controlled the vast lands of the Persian Empire, but with the agreement of his men, he kept moving eastward. Over the next six years, from 330 to 324 B.C., his armies subdued what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan, and ventured into India. Alexander secured his position in Afghanistan by marrying the Bactrian princess Roxana (d. c. 310 B.C.), but as he became aware that some of his troops were growing weary, he sent the oldest of them home.

He wanted to keep going east as far as he could, simply to see what was there, and if possible, add it to his empire. But in July of 326 B.C., just after they crossed the Beas River in India, his troops refused to go on. There might have been a rebellion if Alexander had tried to force the issue, but he did not. He sent one group, led by Nearchus (d. 312? B.C.), back by sea to explore the coastline as they went, and another by a northerly route. He took a third group through southern Iran, on a journey through the desert in which the entire army very nearly lost its way.

In the spring of 323 B.C., they reached Babylon, and Alexander began plotting the conquest of Arabia. But he was unraveling both physically and emotionally, and he had taken to heavy drinking. He caught a fever, and was soon unable to move or speak. During the last days of his life, Alexander--the man of action--was forced to lie on his bed while all his commanders filed by in solemn tribute to the great man who had led them where no conqueror had ever gone. On June 13, 323 B.C., he died.

Alexander was no ordinary conqueror: his empire seemed to promise a newer, brighter age when the nations of the world could join together as equals. Though some of his commanders did not agree with him on this issue, Alexander made little distinction between racial and ethnic groups: instead, he promoted men on the basis of their ability. From the beginning, his armies had recruited local troops, but with the full conquest of Persia, they stepped up this policy. It was his goal to leave Persia in the control of Persians trained in the Greek language and Greek culture, and he left behind some 70 new towns named Alexandria. Thus began the spread of Hellenistic culture throughout western Asia.

But Alexander's empire did not hold. The generals who succeeded him lacked his vision, and they spent the remainder of their careers fighting over the spoils of his conquests. Seleucus (c. 356-281 B.C.) gained control over Persia, Mesopotamia, and Syria, where an empire under his name would rule for many years, and Ptolemy (c. 365-c. 283 B.C.) established a dynasty of even longer standing in Egypt. His descendants ruled until 30 B.C., when the last of his line, Cleopatra (69-30 B.C.)--also the last Egyptian pharaoh--was defeated by a new and even bigger empire, Rome.