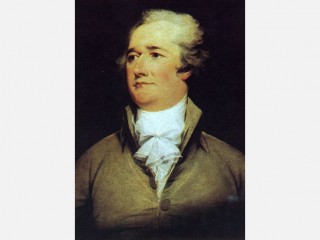

Alexander Hamilton biography

Date of birth : 1755-01-11

Date of death : 1804-07-11

Birthplace : Nevis, British West Indies

Nationality : British

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-11-18

Credited as : Politician, first U.S. secretary of the Treasury,

The first U.S. secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton was instrumental in developing the nation's first political party, the Federalists.

Alexander Hamilton's birth date is disputed, but he probably was born on Jan. 11, 1755, on the island of Nevis in the British West Indies. He was the illegitimate son of James Hamilton, a Scotsman, and Rachel Fawcett Lavien, daughter of a French Huguenot physician.

Hamilton's education was brief. He began working sometime between the ages of 11 and 13 as a clerk in a trading firm in St. Croix. In 1772 he left—perhaps encouraged and financed by his employers—to attend school in the American colonies. After a few months at an academy in New Jersey, he enrolled in King's College, New York City. Precocious enough to master most subjects without formal instruction and eager to win success and fame early in life, he left college in 1776 without graduating.

The outbreak of the American Revolution offered Hamilton the opportunity he craved. In March 1776 he became captain of a company of artillery and, a year later, a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army and aide-de-camp to commanding general George Washington. Hamilton's ability was apparent, and he became one of Washington's most trusted advisers. Although he played no role in major military decisions, Hamilton's position was one of great responsibility. He drafted many of Washington's letters to high-ranking Army officers, the Continental Congress, and the states. He also was sent on important military missions and

drafted major reports on the reorganization and reform of the Army. Despite the demands of his position, he found time for reading and reflection and expressed his ideas on economic policy and governmental debility in newspaper articles and in letters to influential public figures.

In February 1781, in a display of pique at a minor reprimand by Gen. Washington, Hamilton resigned his position. Earlier, on Dec. 14, 1780, he had married the daughter of Philip Schuyler, a member of one of New York's most distinguished families. In July 1781 Hamilton's persistent search for active military service was rewarded when Washington gave him command of a battalion of light infantry in the Marquis de Lafayette's corps. After the Battle of Yorktown, Hamilton returned to New York. In 1782, following a hasty apprenticeship, he was admitted to the bar.

During the Revolution, Hamilton's ideas on government, society, and economic matured. These were conditioned by his foreign birth, which obviated a strong attachment to a particular state or locality, and by his presence at Washington's headquarters, where he could see the war as a whole. Like the general himself, Hamilton was deeply disturbed that the conduct of the war was impeded by the weakness of Congress and by state and local jealousies. It was this experience rather than any theoretical commitment to a particular form of government that structured Hamilton's later advocacy of a strong central government.

From the end of the Revolution to the inauguration of the first government under the Constitution, Hamilton tirelessly opposed what he described as the "dangerous prejudices in the particular states opposed to those measures which alone can give stability and prosperity to the Union." Though his extensive law practice won him recognition as one of New York's most distinguished attorneys, public affairs were his major concern.

Attending the Continental Congress as a New York delegate from November 1782 through July 1783, he unsuccessfully labored, along with James Madison and other nationalists, to invest the Confederation with powers equal to the needs of postrevolutionary America. Convinced that the pervasive commitment to states' rights obviated reform of the Articles of Confederation, Hamilton began to advocate a stronger and more efficient central government. As one of the 12 delegates to the Annapolis Convention of 1786, he drafted its resolution calling for a Constitutional Convention "to devise such further provisions as shall appear … necessary to render the Constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union. … " Similarly, as a member of the New York Legislature in 1787, he was the eloquent spokesman for continental interests as opposed to state and local ones.

Hamilton was one of the New York delegates to the Constitutional Convention, which sat in Philadelphia from May to September 1787. Although he served on several important committees, his performance was disappointing, particularly when measured against his previous (and subsequent) accomplishments. His most important speech called for a government close to the English model, one so high-toned that it was unacceptable to most of the delegates.

Hamilton's contribution to the ratification of the Constitution was far more important. In October 1787 he determined to write a series of essays on behalf of the proposed Constitution. First published in New York City newspapers under the pseudonym "Publius" and collectively designated The Federalist, these essays were designed to persuade the people of New York to ratify the Constitution. Though The Federalist was written in collaboration with John Jay and James Madison, Hamilton wrote 51 of the 85 essays. First published in book form in 1788, the Federalist essays have been republished in many editions and languages. They constitute one of America's most original and important contributions to political philosophy and remain today the authoritative contemporary exposition of the meaning of the cryptic clauses of the U.S. Constitution. At the New York ratifying convention in 1788, Hamilton led in defending the proposed Constitution, which, owing measurably to Hamilton's labors, New York ratified.

On Sept. 11, 1789, some 6 months after the new government was inaugurated, Hamilton was commissioned the nation's first secretary of the Treasury. This was the most important of the executive departments because the new government's most pressing problem was to devise ways of paying the national debt—domestic and foreign—incurred during the Revolution.

Hamilton's program, his single most brilliant achievement, also created the most bitter controversy of the first decade of American national history. It was spelled out between January 1790 and December 1791 in three major reports on the American economy: "Report on the Public Credit"; "Report on a National Bank"; and "Report on Manufactures."

In the first report Hamilton recommended payment of both the principal and interest of the public debt at par and the assumption of state debts incurred during the American Revolution. The assumption bill was defeated initially, but Hamilton rescued it by an alleged bargain with Thomas Jefferson and Madison for the locale of the national capital. Both the funding and assumption measures became law in 1791 substantially as Hamilton had proposed them.

Hamilton's "Report on a National Bank" was designed to facilitate the establishment of public credit and to enhance the powers of the new national government. Although some members of Congress doubted this body's power to charter such a great quasi-public institution, the majority accepted Hamilton's argument and passed legislation establishing the First Bank of the United States. Before signing the measure, President Washington requested his principal Cabinet officers, Jefferson and Hamilton, to submit opinions on its constitutionality. Arguing that Congress had exceeded its powers, Jefferson submitted a classic defense of a strict construction of the Constitution; affirming the Bank's constitutionality, Hamilton submitted the best argument in American political literature for a broad interpretation of the Constitution.

The "Report on Manufactures, " his only major report which Congress rejected, was perhaps Hamilton's most important state paper. The culmination of his economic program, it is the clearest statement of his economic philosophy. The protection and encouragement of infant industries, he argued, would produce a better balance between agriculture and manufacturing, promote national self-sufficiency, and enhance the nation's wealth and power.

Hamilton also submitted other significant reports which Congress accepted, including a plan for an excise on spirits and a report on the establishment of a Mint. Hamilton's economic program was not original (it drew heavily, for example, upon British practice), but it was an innovative and creative application of European precedent and American experience to the practical needs of the new country.

Hamilton's importance during this period was not confined to his work as finance minister. As the virtual "prime minister" of Washington's administration, he was consulted on a wide range of problems, foreign and domestic. He deserves to be ranked, moreover, as the leader of the country's first political party, the Federalist party. Hamilton himself, like most of his contemporaries, railed against parties and "factions, " but when the debate over his fiscal policies revealed a deep political division among the members of Congress, Hamilton boldly assumed leadership of the proadministration group, the Federalists, just as Jefferson provided leadership for the Democratic Republicans.

Because of the pressing financial demands of his growing family, Hamilton retired from office in January 1795. Resuming his law practice, he soon became the most distinguished member of the New York City bar. His major preoccupation remained public affairs, however, and he continued as President Washington's adviser. The latter's famous "Farewell Address" (1796), for example, was largely based on Hamilton's draft. Nor could Hamilton remain aloof from politics. In the election of 1796 he attempted to persuade the Federalist electors to cast a unanimous vote for John Adam's running mate, Thomas Pinckney.

The high regard in which most of the country's leading Federalists held Hamilton was matched by the dislike and distrust with which many others—notably the Republicans—viewed him. He was ambitious, arrogant, and opinionated. He was also indiscreet. For example, to refute a baseless charge by James Reynolds and others that as secretary of the Treasury he was guilty of corruption, he needlessly published a defense which included a confession of adultery with Mrs. Reynolds. Such an admission undoubtedly diminished the possibility of political preferment.

During the presidency of John Adams, however, Hamilton continued to wield considerable national influence, for members of Adams's Cabinet often sought and followed his advice. In 1798 they cooperated with George Washington to secure Hamilton's appointment—over Adams's strong opposition—as inspector general and second in command of the newly augmented U.S. Army, which was preparing for a possible war against France. Since Washington declined active command, organizing and recruiting the "Provisional Army" fell to Hamilton. His military career abruptly came to an end in 1800 after John Adams, in the face of the opposition of his Cabinet and other Federalist leaders (Hamilton among them), sent a peace mission to France that negotiated a settlement of the major issues.

Hamilton's role in the presidential campaign of 1800 not only was a disservice to his otherwise distinguished career but also seriously wounded the Federalist party. Convinced of John Adam's ineptitude, Hamilton rashly published a long Philippic which characterized the President as a man possessed by "vanity without bounds, and a jealousy capable of discoloring every object, " with a "disgusting egotism" and an "ungovernable discretion of … temper." Instead of discrediting Adams, the pamphlet promoted election of the Republican candidates, Jefferson and Aaron Burr. When the Jefferson-Burr tie went for decision to the House of Representatives, however, Hamilton regained his balance. Convinced that Jefferson would not undermine executive authority, Hamilton also believed that Burr was "the most unfit and dangerous man of the community." He accordingly used his considerable influence to persuade congressional leaders to select Jefferson.

Although his interest in national policies and politics was unabated, Hamilton's role in national affairs after 1801 diminished. He remained a prominent figure in the Federalist party, however, and published his opinions on public affairs in the New York Evening Post. He was still an ardent nationalist and in 1804 severely condemned the rumored plot of New England and New York Federalists to dismember the Union by forming a Northern confederacy. Believing Aaron Burr to be a party to this scheme, Hamilton actively opposed the Vice President's bid for the New York governorship. He was successful, and Burr, now out of favor with the Jefferson administration and discredited in his own state, charged that Hamilton's remarks had impugned his honor. Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel. Although Hamilton was reluctant, he believed that his "ability to be in future useful" demanded his acceptance. After putting his personal affairs in order, he met Burr at dawn on July 11, 1804, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River. The two exchanged shots, and Hamilton fell, mortally wounded. Tradition has it that he deliberately misdirected his fire, leaving himself an open target for Burr's bullet. Hamilton was carried back to New York City, where he died the next afternoon.

Henry Cabot Lodge, ed., The Works of Alexander Hamilton (2d ed., 12 vols., 1903), will be replaced by Harold C. Syrett and Jacob E. Cooke, eds., Papers, 15 volumes of which have been published (1961-1969). Hamilton's definitive biography is Broadus Mitchell's meticulous Alexander Hamilton (2 vols., 1957-1962). John C. Miller, Alexander Hamilton (1959), is an excellent one-volume life. Useful biographies are David Loth, Alexander Hamilton: Portrait of a Prodigy (1939), and Nathan Schachner, Alexander Hamilton (1946). Also recommended are Claude G. Bowers, Jefferson and Hamilton: The Struggle for Democracy in America (1925), and Richard B. Morris, Alexander Hamilton and the Founding of the Nation (1957).