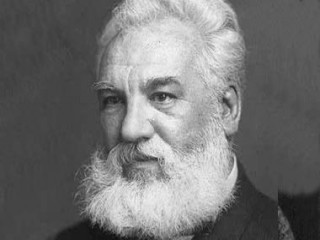

Alexander Graham Bell biography

Date of birth : 1847-03-03

Date of death : 1922-08-02

Birthplace : Edinburg, Scotland, UK

Nationality : Canadian

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2010-07-29

Credited as : Scientist and engineer, inventor of the telephone, teacher and innovator

30 votes so far

The young man

Alexander Graham Bell was born on March 3, 1847, in Edinburgh, Scotland. His father, Alexander Melville Bell, was an expert on the mechanics of the voice and on elocution (the art of public speaking). His grandfather, Alexander Bell, was an elocution professor. Bell's mother, Eliza, was hard of hearing but became an accomplished pianist (as well as a painter), and Bell took an interest in music. Eliza taught Alexander, who was the middle of three brothers, until he was ten years old. When he was a youth he took a challenge from a mill operator and created a machine that removed the husks from grain. He would later call it his first invention.

After studying at the University of Edinburgh and University College, London, England, Bell became his father's assistant. He taught the deaf to talk by adopting his father's system of visible speech (illustrations of speaking positions of the lips and tongue). In London he studied Hermann Ludwig von Helmholtz's (1821–1894) experiments with tuning forks and magnets to produce complex sounds. In 1865 Bell made scientific studies of the resonance (vibration) of the mouth while speaking.

Both of Bell's brothers had died of tuberculosis (a fatal disease that attacks the lungs). In 1870 his parents, in search of a healthier climate, convinced him to move with them to Brantford, Ontario, Canada. In 1871 he went to Boston, Massachusetts, to teach at Sarah Fuller's School for the Deaf, the first such school in the world. He also tutored private students, including Helen Keller (1880–1968). As professor of voice and speech at Boston University in 1873, he initiated conventions for teachers of the deaf. Throughout his life he continued to educate the deaf, and he founded the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf.

Inventing the telephone

From 1873 to 1876 Bell experimented with many inventions, including an electric speaking telegraph (the telephone). The funds came from the fathers of two of his students. One of these men, Gardiner Hubbard, had a deaf daughter, Mabel, who later became Bell's wife.

To help deaf children, Bell experimented in the summer of 1874 with a human ear and attached bones, magnets, smoked glass, and other things. He conceived the theory of the telephone: that an electric current can be made to change its force just as the pressure of air varies during sound production. That same year he invented a telegraph that could send several messages at once over one wire, as well as a telephonic-telegraphic receiver.

Bell supplied the ideas; Thomas Watson created the equipment. Working with tuned reeds and magnets to make a receiving instrument and sender work together, they transmitted a musical note on June 2, 1875. Bell's telephone receiver and transmitter were identical: a thin disk in front of an electromagnet (a magnet created by an electric current).

On February 14, 1876, Bell's attorney filed for a patent, or a document guaranteeing a person the right to make and sell an invention for a set number of years. The exact hour was not recorded, but on that same day Elisha Gray (1835–1901) filed his caveat (intention to invent) for a telephone. The U.S. Patent Office granted Bell the patent for the "electric speaking telephone" on March 7. It was the most valuable single patent ever issued. It opened a new age in communications technology.

Bell continued his experiments to improve the telephone's quality. By accident, Bell sent the first sentence, "Watson, come here; I want you," on March 10, 1876. The first public demonstration occurred at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences convention in Boston two months later. Bell's display at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition a month later gained more publicity. Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil (1825–1891) ordered one hundred telephones for his country. The telephone, which had been given only eighteen words in the official catalog of the exposition, suddenly became the "star" attraction.

Establishing an industry

Repeated demonstrations overcame public doubts. The first two-way outdoor conversation was between Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, by Bell and Watson on October 9, 1876. In 1877 the first telephone was installed in a private home; a conversation took place between Boston and New York using telegraph lines; in May the first switchboard (a central machine used to connect different telephone lines), devised by E. T. Holmes in Boston, was a burglar alarm connecting five banks; and in July the first organization to make the telephone a commercial venture, the Bell Telephone Company, was formed. That year, while on his honeymoon, Bell introduced the telephone to England and France.

The first commercial switchboard was set up in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1878, the same year Bell's New England Telephone Company was organized. Charles Scribner improved switchboards, with more than five hundred inventions. Thomas Cornish, a Philadelphia electrician, had a switchboard for eight customers and published a one-page telephone directory in 1878.

Questioning Bell's patent

Other inventors had been at work between 1867 and 1873. Professor Elisha Gray (of Oberlin College in Ohio) invented an "automatic self-adjusting telegraph relay," installed it in hotels, and made telegraph printers. He also tried to perfect a speaking telephone from his multiple-current telegraph. The Gray and Batton Manufacturing Company of Chicago developed into the Western Electric Company.

Another competitor was Professor Amos E. Dolbear, who insisted that Bell's telephone was only an improvement on an 1860 invention by Johann Reis, a German who had experimented with pigs' ears and may have made a telephone. Dolbear's own instrument could transmit tones but not voice quality.

In 1879 Western Union, with its American Speaking Telephone Company, ignored Bell's patents and hired Thomas Edison (1847–1931), along with Dolbear and Gray, as inventors and improvers. Later that year Bell and Western Union formed a joint company, with the latter getting 20 percent for providing wires, equipment, and the like. Theodore Vail, organizer of Bell Telephone Company, combined six companies in 1881. The modern transmitter was born mainly in the work of Emile Berliner and Edison in 1877 and Francis Blake in 1878. Blake's transmitter was later sold to Bell.

The claims of other inventors were contested. Daniel Drawbaugh, who was from rural Pennsylvania and had little formal schooling, almost won a legal battle with Bell in 1884 but was defeated by a four-to-three vote in the Supreme Court (the highest court in the United States). This claim made for the most exciting lawsuit over telephone patents. Altogether the Bell Company was involved in 587 lawsuits, of which five went to the Supreme Court. Bell won every case. The defending argument for Bell was that no competitor had claimed to be original until seventeen months after Bell's patent. Also, at the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, major electrical scientists, especially Lord Kelvin (1824–1907), the world's leading authority, had declared Bell's invention to be "new." Professors, scientists, and researchers defended Bell, pointing to his lifelong study of the ear and his books and lectures on speech mechanics.

The Bell Company

The Bell Company built the first long-distance line in 1884, connecting Boston and New York. Bell and others organized The American Telephone and Telegraph Company in 1885 to operate other long-distance lines. By 1889 there were 11,000 miles of underground wires in New York City.

The Volta Laboratory was started by Bell in Washington, D.C., with France awarding the Volta Prize money (about $10,000) for his invention. At the laboratory Bell and his associates worked on various projects during the 1880s, including the photophone, induction balance, audiometer, and phonograph improvements. The photophone transmitted speech by light. The induction balance (electric probe) located metal in the body. The audiometer, used to test a person's hearing, indicated Bell's continued interest in deafness. The first successful phonograph record was produced. The Columbia Gramophone Company made profitable Bell's phonograph records. With the profits Bell established an organization in Washington to study deafness.

Bell's later interests

Bell was also involved in other activities that took much of his time. The magazine Science (later the official publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science) was founded in 1880 because of Bell's efforts. He made many addresses and published many papers. As National Geographic Society president from 1896 to 1904, he contributed to the success of the society and its publications. In 1898 he became a member of a governing board of the Smithsonian Institution. He was also involved in sheep breeding, hydrodynamics (the study of the forces of fluids, such as water), and projects related to aviation, or the development and design of airplanes.

Aviation was Bell's primary interest after 1895. He aided physicist and astronomer Samuel Langley (1834–1906), who experimented with heavier-than-air flying machines; invented a special kite (1903); and founded the Aerial Experiment Association (1907), bringing together aviator and inventor Glenn Curtiss (1878–1930), Francis Baldwin, and others. Curtiss provided the motor for Bell's man-carrying kite in 1907.

Bell died in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, Canada, on August 2, 1922. His contribution to the modern world and its technologies was enormous.