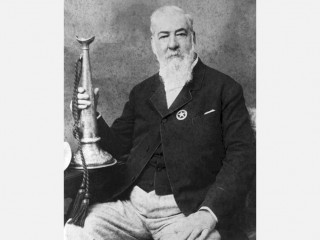

Alexander Cartwright biography

Date of birth : 1820-04-17

Date of death : 1982-07-12

Birthplace : New York City, New York, US

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-11-17

Credited as : Sportsman, official inventor of the modern game of baseball,

Contrary to the official myth about the origin of the sport, Alexander Cartwright (1820-1898) is the man who should be credited with doing the most to invent the modern game of baseball. In 1845, Cartwright laid out the key rules of the game, including the dimensions of the field. He was enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame even as baseball's establishment propagated a myth that Civil War General Abner Doubleday invented baseball.

In 1846, Cartwright and other members of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club played the first recognized baseball game in Hoboken, New Jersey, at a park called the Elysian Fields. Cartwright later traveled west across the United States, spreading the game as far as California and Hawaii. But during his lifetime he was never properly credited by organized baseball for his pioneering efforts.

Baseball, commonly called America's national pastime, was adapted from a British game known as "rounders." Rounders was a simplified offshoot of cricket, and it was played primarily by children in Britain and in the British colonies of North America in the 1700s (and later in the United States in the 1800s). It was also sometimes called "base ball." Adults in some colonies, such as Massachusetts, played a version known as "town ball." In all these pick-up games, a pitcher threw a ball, an opponent used a stick or bat to strike it, and then the hitter attempted to run to one or more bases. Runners were "put out" when fielders threw the ball and hit them; this was called "soaking." There were few if any standard rules to the game, and the number of players on a team, the number of bases, and the distances between the bases were largely a matter of local custom or pre-game negotiations.

Alexander Cartwright was born in New York City on April 17, 1820. After leaving school at the age of 16, he became a clerk at a bank. Later on, he also became a volunteer fireman. In the evenings, Cartwright joined other young New York businessmen, lawyers and doctors who got together to play a version of rounders. Their sport came to be known as the "New York game" to distinguish it from the "Massachusetts game" of "town ball."

For several years, Cartwright belonged to a group called the New York Base Ball Club. In 1845, some members of that group joined with others and organized a new group, the Knickerbocker Club. Cartwright was appointed secretary and vice-president of the club when it wrote down a formal constitution in September of that year.

Cartwright took a leadership role in suggesting to other members of the Knickerbocker Club that they write down a set of rules for the game they played. Up until then the traditions of the game had been passed down orally but never codified. Cartwright was one of four members who decided upon 14 written rules. The dimensions of Madison Square, where the Knickerbocker Club most often played, necessitated the most important rules. One rule eliminated the circular field common to cricket and established fair and foul territory. The club members limited the number of bases to four (including home plate), fixed them in the shape of a diamond, and set them 90 feet apart. Cartwright and the other Knickerbocker rule makers also outlawed the practice of soaking, because they considered it rude and ungentle-manly. The more genteel activities of tagging a runner with the ball, or getting the ball to a base before a runner reached that base, became the accepted ways to retire a runner.

Cartwright later was credited with instituting two other key rule changes: setting the number of players at nine for each side, and fixing the length of a game at nine innings. But baseball historians dispute whether Cartwright and the other Knickerbocker rule makers really should be credited with these innovations. For the first several years of their existence, the Knickerbockers usually played with eight men-three infielders (one standing near each base), three outfielders, a pitcher and a catcher. In other games they used 9, 10 or even 12 players. The position of shortstop apparently was not solidified until 1849, when it was established as a means of relaying throws from the outfield to the infield. (The ball used at the time was so light that players could not throw it all the way in from the outfield with one throw.) As far as the length of the game, it was not until 1857 that a convention of ball players decided upon nine innings; up until then, the first team to score 21 runs was generally the winner.

Once the Knickerbockers had agreed upon their rules, they began advertising for games. Their first opponent was a team called the New York Nine. On June 19, 1846, the teams traveled from Manhattan across the Hudson River to Hoboken, New Jersey, and played the first recognized baseball game at a park known as the Elysian Fields. Cartwright, who wrote in his diary that he was one of the best Knickerbocker players, did not play in the first game. Instead, he served as umpire and collected a six-cent fine from any player who used profanity. Ironically, the Knickerbockers lost the game, under the rules they had invented, by the decisive score of 23 to 1.

Cartwright remained with the Knickerbockers for four more years, during which the team played many other games with the New York Nine and other local clubs. Records of the games and of Cartwright's play are unavailable. Under the leadership of Cartwright and the other Knickerbockers, baseball soon became a favorite pastime for many young New York men. In those years it was not played by factory workers (who had no time or energy after their 12-hour or longer days) but mainly by clerks, attorneys, physicians and businessmen who had time after work to play in the late afternoons.

By early 1949, Cartwright, like thousands of other Americans, came down with a bad case of gold fever after hearing of the discoveries of gold in California. On March 1, he headed west, never to return to New York. As he journeyed across the country by train, by wagon and by foot, he took the game of baseball with him. Like the legendary Johnny Appleseed, Cartwright spread seeds for the sport that had become so popular in a few eastern cities. Among his stops was Cincinnati, which would be a cornerstone of the National League when it was formed in 1876. He made his way across the Great Plains and taught the sport of baseball to locals in many places. In August he arrived in San Francisco, but by then the great gold rush was over.

Cartwright remained in San Francisco for six weeks, hoping that he still might strike gold somewhere. During that time he helped to establish the game of baseball in that city. He finally decided to return to New York, this time on a ship sailing across the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans. But he fell ill and was put ashore in Hawaii, then known as the Sandwich Islands.

Cartwright recovered from his illness and fell in love with the islands. He began teaching the islanders how to play baseball and forming local leagues. As a result of his activity, baseball became firmly established in Honolulu well before it was introduced to cities such as Detroit and Chicago. Back in New York City, the Knickerbockers and other clubs continued to play, and the game soon became popular all around the country. During the Civil War, troops played baseball during breaks in combat.

Cartwright's wife and children joined him in 1851. He founded the Honolulu Fire Department and served as the city's fire chief for ten years. Cartwright set up a number of businesses and became a wealthy man as well as a civic leader. He served in several government positions, and helped to establish the islands' library system and one of its foremost hospitals.

Cartwright never returned to the mainland to witness the spread of the game that he was so instrumental in popularizing. He died in Honolulu on July 12, 1898— largely unknown to the outside world. The first diamond he laid out is now called Cartwright Field. His grave has been visited by many famous baseball players, including Babe Ruth.

Cartwright's place in baseball history was ignored for many decades. In the mid-1930s, the National Baseball Hall of Fame was opened in Cooperstown, New York. A commission of high-ranking baseball officials was set up to determine who should be credited with inventing the game. The real history of the sport was largely lost, but the commission was eager to discredit any link to the British sport of cricket. The commission fixated on an apocryphal story involving a Civil War hero, General Abner Doubleday. According to a myth that the leaders of baseball sanctioned, Doubleday invented baseball in a cow pasture in Cooperstown in 1838. Since the Hall of Fame was set to open in 1938, the story was a convenient fabrication—it posited that the museum was located in the birthplace of baseball, and that its opening would be a centennial. The commission ignored facts about baseball's true origins because it was determined that a genuine American hero be credited with inventing the national pastime.

When Cartwright's descendants heard about the Doubleday story, they registered a protest. Cartwright's grandson gave the Hall of Fame his grandfather's diaries as well as news clippings and other items that substantiated the role of Cartwright and the Knickerbockers in codifying many of the game's most important rules. However, the newspapers of the era carefully toed the official line because so much publicity had already been disseminated about Doubleday. So the public came to believe that Doubleday invented baseball. In fact, the general's connection to baseball was so tenuous that most historians believe he never even attended a game.

With little fanfare, Cartwright was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1939. His plaque characterizes him as the "Father of Modern Base Ball." Doubleday, however, was never enshrined in the Hall of Fame. Yet baseball's officials never took any other action to recant the Doubleday myth. The fabrication took on the status of received truth. The field at Cooperstown is still called Doubleday Field. And more than 60 years later, most Americans continued to believe that Doubleday was baseball's inventor.

The truth is more complicated. No single person invented baseball. It was adapted from rounders and gradually shaped into a distinctive American sport. But as a leader of the Knickerbockers, the man who first set down rules in writing, and the game's first traveling ambassador, Alexander Cartwright fully deserves credit as baseball's founding father.

Peterson, Harold, The Man Who Invented Baseball, Scribner, 1973.