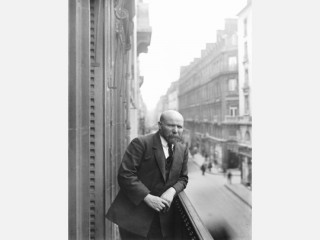

Albert Kahn biography

Date of birth : 1869-03-21

Date of death : 1942-12-08

Birthplace : Rhaunen, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Nationality : American

Category : Arhitecture and Engineering

Last modified : 2010-11-13

Credited as : Architect, father of the modern American factory,

Architech Albert Kahn has been called the father of the modern American factory. The factories that he designed for many Detroit manufacturers were known for their streamlined forms and functionalities.

Detroit-based architect Albert Kahn has been called the father of the modern American factory. By the 1920s Detroit had become the center of the flourishing U.S. automobile industry, and Kahn provided what he described as "beautiful factories"—streamlined and functional—for many of the great Detroit manufacturers. Packard, Chrysler, General Motors, and Ford were among his clients, as were giants in such worldwide industries as food, textiles, chemicals, and business machines. During the early 1930s Kahn helped establish factories and engineering education in the Soviet Union; later in the 1930s and in the first years of World War II he developed plants for the construction of tanks and military aircraft. Throughout his career he also designed notable nonindustrial structures: the Detroit Athletic club, office buildings for General Motors and Fisher, the Hill Auditorium and Clements Library at the University of Michigan, and handsome private homes for such Grosse Pointe auto magnates as H. E. Dodge and Edsel Ford. But it is for his more than two thousand factories that Albert Kahn is remembered.

Kahn, the oldest son of an itinerant rabbi, was born in Germany but spent his early childhood in Luxembourg. In 1880 the family immigrated to Detroit, where young Kahn did not attend school but instead worked at odd jobs and took free Sunday-morning art lessons from sculptor Julius Melchers. Discovering that his pupil was color-blind, Melchers recommended that he take up architecture instead of art and in 1885 helped him earn an apprentice position with the Detroit firm of Mason and Rice. Kahn proved an apt student of design and in 1890 won a scholarship that allowed him to travel for a year in Europe, where he met and became friends with another young architect, Henry Bacon. Returning to Detroit, Kahn rose to the position of chief designer with Mason and Rice. He refused an offer to replace Frank Lloyd Wright in Louis Sullivan's firm during the early 1890s, instead remaining with Mason and Rice until 1896. In that year he married Ernestine Krolik and set up an architectural partnership with two colleagues from Mason and Rice. By 1902 Kahn had established his own practice, which grew during the next forty years to a company of nearly four hundred people.

Kahn's first significant industrial commission came from Henry B. Joy, manager of the Packard Motor Car Company, who asked him to design a ten-building production plant in Detroit. Completed between 1903 and 1905, the project included nine conventional buildings and a tenth constructed of reinforced concrete, a material that had rarely been used before in factory construction. In 1908 Henry Ford had introduced the Model T, and late that year Ford contracted with Kahn to design a factory that would place all aspects of the auto's production under a single roof. This Highland Park construction (1909-1914) combined reinforced concrete with large, steel-framed windows, thus providing improved lighting and ventilation for assembly-line workers. Through this project Kahn and Ford established a long and mutually beneficial relationship: both were energetic, inventive, self-educated men who sought innovative but practical solutions to problems in the workplace.

In early 1918 Ford asked Kahn to design and construct a single-building production plant for the Eagle Submarine Chaser, which Ford wanted to produce as part of the U.S. war effort. In fourteen weeks Kahn erected a huge, one-story, steel-framed, lavishly windowed structure on a new two-thousand-acre Ford site on the Rouge River near Detroit. After the war the building was converted to a Model T body shop, and its site became the nucleus of Ford's expanding empire. Between 1922 and 1926 Kahn constructed at River Rouge a complex of innovative factory buildings, including the Glass Plant (1922), the Motor Assembly Building (1924-1925), and the Open Hearth Building (1925). In most cases these one-story structures incorporated steel frames, windowed walls, roofs with monitors (raised sections containing additional windows or louvers), and interior planning built around assembly-line organizational systems. Clean and attractive, River Rouge was America's first truly modern industrial complex because its design and construction fully expressed the architecture of utility.

Following the stock-market crash in October 1929, automobile production radically declined, but Kahn and his company remained busy renovating plants so that they could produce vehicles in the most economical way possible. Between 1929 and 1932 he also directed the construction of 521 factories and the training of more than four thousand engineers in the Soviet Union as part of the Soviets' First Five-Year Plan of industrialization. By 1937 Kahn's firm was performing nearly one-fifth of all architect-designed factory construction in the United States. And as World War II approached he developed Ford's giant Willow Run bomber plant (1941-1943), the Glenn Martin Assembly Building and its additions (1937-1941) for the manufacture of other military aircraft, and the Chrysler Tank Arsenal (1941), all models of modern design. In the course of his career Albert Kahn seized the opportunity—and the responsibility—to transform the architecture of American industry. Toward the end of his life he recalled, with obvious satisfaction and with tongue firmly in cheek: "When I began, the real architects would design only museums, cathedrals, capitols, monuments. The office boy was considered good enough to do factory buildings. I'm still that office boy designing factories. I have no dignity to be impaired."