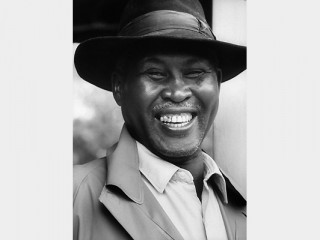

Albert John Luthuli biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : 1967-07-21

Birthplace : Rhodesia, South Africa

Nationality : South African

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-11-13

Credited as : Politician and statesman, first South African who received the Nobel Peace Prize,

Albert John Luthuli was a South African statesman and the first African to win the Nobel Prize for peace. His leadership of black resistance to apartheid helped to focus world opinion on South Africa's race policies.

Albert Luthuli was born in Solusi mission station, Rhodesia, where his father served American missionaries as an interpreter. The Luthulis had originally come from Groutville, a Zulu mission station about 40 miles to the north of Durban. Young Albert attended school in Groutville and trained as a teacher at Adams College, where he later taught. It was while he was teaching at Adams that the Groutville community requested him to become its chief. Sugarcane production, which was the reservation's main source of income, had run into difficulties. Luthuli accepted the invitation and saved the community's economy from collapse.

Luthuli's thinking was influenced as much by the Zulu's view of life as by his Christian background and by race segregation. These made his regard for the sacredness of the person and his commitment to nonviolence and the creation of a nonracial democracy in South Africa the dominant features of his leadership.

Luthuli regarded the traditional evaluation of the person as transcending all barriers of race because the infinite consciousness has no color. Black and white are bound together by the common humanity they have. He believed that Christian values can unite black and white in a democratic coalition. Apartheid's preoccupation with color and the particular experience of the Afrikaner outraged him because it gives a meaning to Christian values which uses race to fix the person's position in society and sets a ceiling beyond which the African cannot develop his full potential as a human being. In this setting the black man (or any other person of color) is punished for being the child of his parents. Luthuli rejected violence not only because it militates against the coalition he had in mind but also because it offends the Golden Rule.

For holding these views Luthuli was later to be deposed, banned, and brought to trial for treason. The law under which he was charged (1956) was the Suppression of Communism Act. South African law recognizes two forms of communism: the Marxist-Leninist and the statutory. Whoever opposes apartheid with determination or advocates race equality seriously is a statutory Communist.

Luthuli was interested in the human experience as a totality. He translated his beliefs into action by supporting the nonracial Christian Council of South Africa, which sent him to the conference of the International Missionary Council held in India in 1938. Ten years later he was in the

United States representing his Congregational Church at the synod of the North American Missionary Conference.

In the meantime Luthuli had involved himself directly in his people's political struggle and, in 1946, had been elected to the Natives Representative Council, a body set up by James Munnik Hertzog to advise the government on African affairs. Luthuli became president of the Natal section of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1951. In this capacity he led the 1951-1952 campaign for the deflance of six discriminatory laws. For doing this he was deposed as chief. In a statement issued after his dismissal he said, "I have joined my people in the spirit that revolts openly and boldly against injustice and expresses itself in a determined and nonviolent manner."

The Africans replied to the dismissal by electing him president general of the ANC. The government countered with a ban which confined him to Groutville for two years. A second ban restricted his movements when the first expired in 1954. Two years later a charge of treason, which collapsed in court after a year's trial, was brought against him and some of his colleagues. Three years later he was banned for five years under the Suppression of Communism Act.

By 1959 Luthuli was coming under criticism from the militants for both his insistence on nonviolence and his form of collaboration with non-Africans. The final split came when Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe broke away from the ANC and formed the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC). On March 21, 1960, Sobukwe called the Africans out in a national demonstration against the Pass Laws. The police opened fire on the demonstrators in Sharpeville, Cape Town, Clermont Township near Pinetown, and Durban. Luthuli proclaimed a day of mourning and was subsequently arrested during the state of emergency which followed the shootings.

The Swedish Parliament nominated Luthuli for the Nobel Peace Prize, which he received at Oslo University on Dec. 10, 1961. In his acceptance speech he stressed the element of continuity in his people's struggle and reaffirmed his hopes for Africa. "I did not initiate the struggle to extend the area of human freedom in South Africa; other African patriots—devoted men—did so before me." He continued, "Our goal is a united Africa in which the standards of life and liberty are constantly expandin…. a nonracial democratic South Africa which upholds the rights of all who live in our country." He invited "Africa to cast her eyes beyond the past and to some extent the present" to the "recognition and preservation of the rights of man and the establishment of a truly free world."

The United States offered Luthuli sanctuary if he decided not to return to South Africa. He did not accept the offer. He was involved in a train accident and died in Stanger on July 21, 1967.

In his autobiography, Let My People Go (1962), Luthuli describes the influences that shaped his thinking. Edward Callan, Albert John Luthuli and the South African Race Conflict (1962), is an informative monograph on Luthuli's public life. For further background consult Anthony Sampson, The Treason Cage: The Opposition on Trial in South Africa (1958); Gwendolen M. Carter, The Politics of Inequality: South Africa since 1948 (1958); and two works by Mary Benson, Chief Albert Luthuli of South Africa (1963) and The African Patriots: The Story of the African National Congress (1963). A chapter on Luthuli is in Melville Harcourt, Portraits of Destiny (1966).