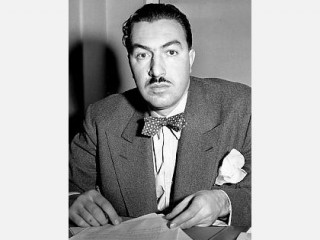

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. biography

Date of birth : 1908-11-29

Date of death : 1972-04-04

Birthplace : New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-11-08

Credited as : Politician and leader, minister,

The political leader and Harlem Baptist minister Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (1908-1972) was a pioneer in civil rights for black Americans.

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. was born on November 29, 1908, in New Haven, Connecticut, moving with his parents at the age of six to Harlem, New York City. His father was a successful clergyman and a dabbler in real-estate. Adam was sent to Hamilton, New York, to Colgate University (1930, A.B.) and afterwards to Columbia University (Teachers College, 1932, M.A.) and studied for the ministry at Shaw University (1935, D.D.).

He was heir-apparent to his father at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem and succeeded him as pastor in 1937. Upon his return to Harlem from Colgate in 1930 he had launched a career of agitation for civil rights, jobs, and housing for African Americans. It was the era of the Depression. He led demonstrations against department stores, Bell Telephone, Consolidated Edison, and Harlem Hospital, among others, to hire African Americans.

Elected to the city council in 1941, he continued to press for civil rights and for jobs for African Americans in public transportation and the city colleges. As editor of the militant People's Voice from 1942, and with a reputation gained from his church for doing something about the destitute (he directed a soup kitchen and a relief operation that fed and clothed thousands of Harlem indigents), he was a force to be reckoned with in the Depression. Leader of the largest African American church in the nation (13, 000 members—a sizeable basis of support), he was ready to use his ample skill in political demagoguery and his charisma in defense of African American nationalism. At the age of 15 he had joined Marcus Garvey's African Nationalist Pioneer Movement, so he understood African American nationalism. The Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia had awarded him a gold medallion for his work of relief in Harlem: he wore it everywhere. Powell's picket lines at the headquarters of the World's Fair in the Empire State Building resulted in hundreds of jobs for African Americans in 1939 and 1940.

But it was after his election to Congress that he really made his stand. He took his seat in 1945 for central Harlem. He was the first African American from an Eastern ghetto and the second African American in Congress—the first was William Dawson of Chicago. Dawson was more moderate than Powell.

As a freshman congressman Powell was appalled at being barred from public facilities in the House of Representatives: dining rooms, steam baths, showers, and barber-shop. He instantly used those facilities; with political instinct, he got his staff to use them also. He engaged Southern segregationists in debate. He tried to bring about an end to segregation in the military, to get African American newsmen admitted to the Senate and House press galleries, to introduce legislation to outlaw Jim Crow in transport, and to inform Congress that the Daughters of the American Revolution were practicing discrimination.

The Southern segregationists were mainly in his own party, the Democratic Party. In 1956 Powell supported Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican seeking a second term, and did not go with Adlai E. Stevenson, the Democratic nominee. He advised Stevenson to reject Southern bigots like Long of Louisiana, Eastland of Mississippi, and Tallmadge of Georgia—all of whom were in the Democratic Party. Eisenhower won, and some Democrats were prepared to punish Powell for his defection. Some critics accused him of currying favor with the federal government over alleged tax irregularities by voting for Eisenhower. Many Democrats had switched to the Republican Party for the presidential choice, as he did, but they were not African American congressmen. Powell was his own man.

Nevertheless, Powell was a Democrat; he welcomed the advent of a new president, Democrat John F. Kennedy in 1960, and became the new chairman of the House Committee on Education and Labor. Despite a high absentee record in the House, his accomplishments as chairman were extraordinary. As Powell himself said: "You don't have to be there if you know which calls to make, which buttons to push, which favors to call in." The committee authorized more important legislation than any other: 48 major pieces of social legislation, embodying more than $14 billion. Kennedy's "New Frontier" and Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society" programs were intimately involved with this committee: education, manpower training, minimum wages, juvenile delinquency, and the war on poverty were all at stake. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson both sent Powell letters of thanks.

All the same, Powell claimed something for his African American constituents with each bill that was laid before him: this was the "Powell Amendment." It called for a stop of federal funds to any organization which practiced racial discrimination. As chairman he had great power to block Great Society legislation; he occasionally held his ground until the Powell Amendment was included in the bill.

As an African American politician and minister he was controversial; as a personality he was extravagant and irreverent. He liked the playboy image, the good life. His first wife was Isabel Washington, a Cotton Club dancer; he had to bully his father into consenting (1933). The marriage lasted ten years. "I fear I just outgrew her, " he said. Wife number two was Hazel Scott, a singer and pianist; they had a good life together from 1945 to 1960, when he divorced her. His third wife was Yvette Marjorie Flores Diago, a member of an influential Puerto Rican family. His affairs were front-page news.

In March 1960 he was interviewed on a television show. He happened to call Esther James a "bag woman" during a debate on police corruption. She sued. Powell refused to make a settlement. He ignored all seven subpoenas and eight years of legal battles. He was wanted for criminal contempt of court by New York State. Finally he escaped to Bimini (Bahamas) in 1966, taking his congressional receptionist, Corinne Huff (former Miss Ohio), with him. She had been with him on a trip on the Queen Mary to Europe in 1962 when she was 21, together with Tamara Hall (an associate labor counsel for Education and Labor). A select committee of the House recommended public censure for Powell, a loss of seniority (his chairmanship), and the dismissal of Huff. The House voted to exclude him altogether (March 1967).

At a special election two months later Powell received a stunning victory—and he did not even campaign in Harlem. Contributions from his supporters and profits from a phonograph record ("Keep the Faith, Baby") were used to pay the damages in the James suit. In March 1968 Powell returned to Harlem triumphantly, and in January 1969 he was seated in Congress yet again, although without seniority. The Supreme Court ruled that the House acted unconstitutionally when he was unseated. Powell quipped: "From now on, America will know the Supreme Court is the place where you can get justice."

In 1970 he was defeated in the Democratic primary. He died on April 4, 1972, of prostate cancer; his ashes were scattered over Bimini. His death caused a legal squabble between his current mistress and his estranged third wife. Powell was a pioneer civil rights worker 30 years before it was fashionable; his legacy to African Americans was his "sassiness."

For the best reading about this subject, see Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Adam by Adam (1971). Andy Jacobs' The Powell Affair: Freedom Minus One (1973) is the story of the vote in the House of Representatives (1967) which unseated Powell. There is an obituary in the New York Times, April 5, 1972, which provides additional information.